Oh ¥€$ – This Is Definitely A Museum Worth Visiting

Regular followers of your favourite blogger will know how much I like Tianjin – a city 120km southeast of the capital Beijing. Apart from the horrendous China House museum, there’s pretty well nothing to dislike about this place. But I have to admit that until recently I had no idea about some of the museums it houses; and as my regular followers will know, I am very much “in” to museums and their ilk.

So I was delighted to come across – by chance – the Chinese Museum of Finance which opened just four years ago. It’s a specialist museum dedicated to China’s finance history, general financial knowledge, and the current and future state of the financial industry.

It is housed on the former site of the French Club, which was built in 1932 at 29, North Jiefang Road in the heart of Tianjin’s old Financial City.

It’s only a couple of streets back from the River Hai, and if you cross over the wrought iron French bridge, you can hardly miss it. This street is where the colonial banks of yesteryear built their branches during the treaty-port era and many of the buildings have been retained and are well-preserved. It’s no longer the central business district, and the street has hardly any cars on it, so it’s a pretty peaceful place to wander around.

The museum was the brain child of a financial highflier called Wang Wei. He was executive vice-president of a domestic brokerage when he was only 34, then a banker, a mergers & acquisitions leader and an author. And he even climbed Mount Everest last year at the age of 56. Apparently he got the idea of a finance museum after visiting a similar one in the United States (this is the eighth such one in the world). To date he has set up three similar museums, with a fourth one being planned for the Haidian district of Beijing.

In many respects, the museum is unusual, to put it mildly – but it means the visitor is constantly pleasantly surprised. Even the entrance ticket, which comes in its own little wallet, is a delight…

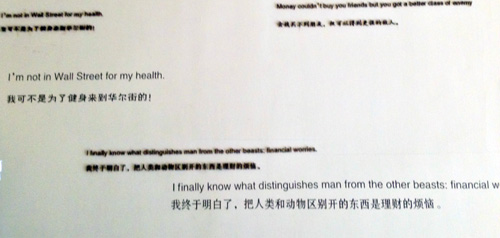

If you were expecting a museum about finance to be dry and boring, then think again. As you enter up the main entrance way staircase, the walls on either side of you are decorated with loads of famous sayings –

Men do not desire merely to be rich, but to be richer than other men / Money will buy a pretty dog, but it won't wag his tail / It's not how much you earn, it's how much you owe / If we command our wealth, we shall be rich and free; if our wealth commands us we are poor indeed / Pennies don't fall from heaven. They have to be earned on earth / and so on and so on…

Inside the lobby area, for want of a better word, the upper walls are decorated with portraits of famous notables in history – Thomas Law, Isaac Newton, Thomas Gresham, as well as numerous Chinese whose names, unfortunately, have not been transliterated as they are elsewhere in the museum.

The whole tone of the museum is upbeat and positive – even to the use of the Yuan, Euro and Dollar to make a point!

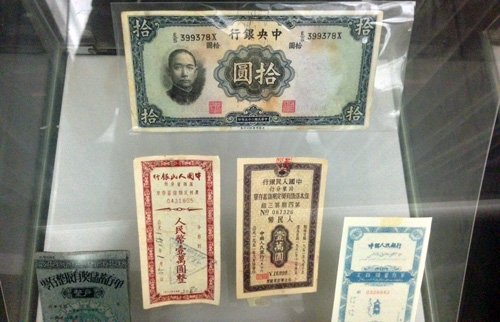

As you would expect in a museum about finance, money is an important theme. The 2,400 sq m exhibition hall stores nearly 200 currencies, banknotes and many other precious finance-related items from China and other countries, from different historical periods.

The museum is divided into five sections, starting with the history and current situation of finance, the origin and development of currency, financial institutions and instruments, financial markets, M&As, and major international financial institutions.

The second part is called “finance and us” and it deals with finance and entrepreneurs, finance and industries, finance and war, finance and politics, finance and science, and finance and the arts.

The third part is the history of Chinese currencies, covering the evolution of currencies in China, and milestones in the history of its finance.

The fourth part deals with financial crises, and is constantly being updated to cover the continuing fall out from the sub-prime crisis, as well as looking back to the Great Depression, the 1987 stock market crash in the US, economic cycles, the 1997 Asian financial crisis, hyperinflation, and financial frauds and scandals.

The final part looks at special topics, including gold and currencies, as well as the history of Tianjin’s North Jiefang Road and the planning of the financial core area in Binhai New Area.

But undoubtedly the stuff that catches one’s attention are the displays of money from all over the world. Obviously there is a preponderance of modern money from the past century…

… but there are also plenty of displays of old forms of currency, and in my view it is vastly better displayed and more “accessible” than the currency museum in Beijing.

There are also Chinese bank notes going back to the declaration of the People’s Republic, including this issue whose 5 and 1 jiao notes are still used to this day. One instinctively feels that the present Mao design on the notes is a retrograde step if you compare it with previous designs.

Most of the foreign money shown has obviously been chosen for the prettiness of their designs, rather than anything more esoteric such as their importance to international finance.

There’s even a display of Disney banknotes…

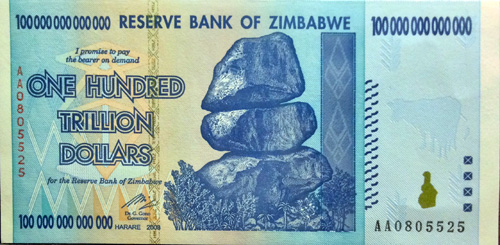

…which might seem odd until you realise that they probably have more worth than the Zimbabwean currency which was printed in hundreds of trillion dollar denominations.

Yes, I did say hundreds of trillions… and yes, that is a One with 14 zeros after it!

All I can say is that the inflation of 1930s Germany (whose bank notes you could count in the hundreds of millions of Marks) didn’t come close to Mugabe’s criminal mishandling of his country’s economy. Somewhere in a box back home I have a whole load of these German inflation notes. I must dig them out and dust them off sometime for a closer look.

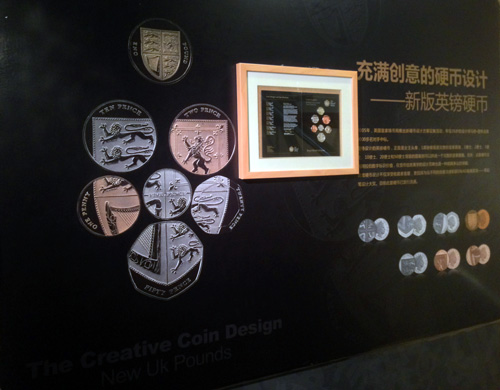

There’s even a beautiful display of the UK’s coinage which took me a bit by surprise.

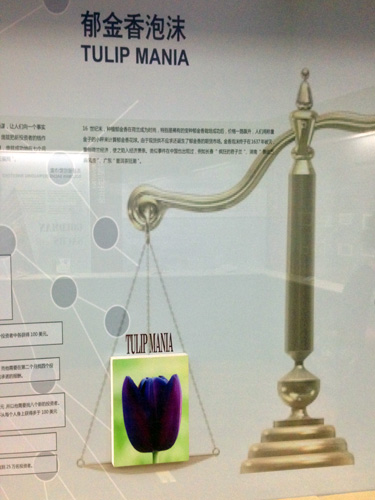

But as I say, this museum is not a currency museum per se. It covers all things financial – including long drawn out explanations (in Chinese only unfortunately) about periods of history where finance would be the lead on the evening news night after night – such as that period in the Netherlands’ history when hyperinflation struck the value of tulip bulbs, which were used as a local currency and swapped hands for thousands of florins depending on their scarcity.

There’s even an abacus which must be one of the largest – if not the largest – in the world. I’ve never seen one so big, though we all know that size isn’t everything!

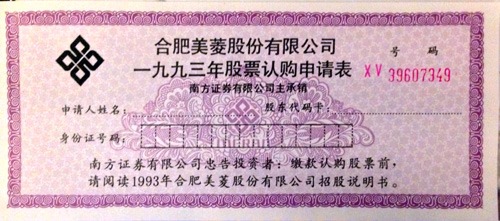

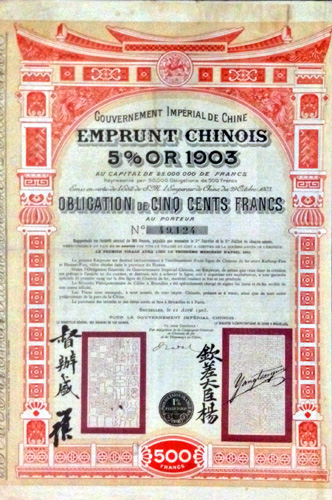

Share certificates, too, get a look in. The museum apparently houses the only known share certificate in existence featuring a picture of Mao Zedong on it. But I didn’t know at the time, which is why you can instead have a look at this Franco-Chinese certificate from 1903, being one of 50,000 such certificates representing a 500 francs share of a total of 250 million francs.

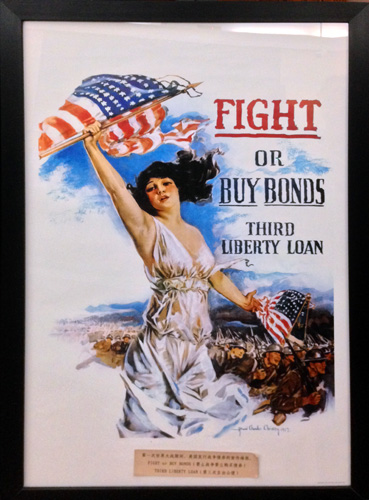

There are also assorted posters which make their own point…

And then every so often you get a corner where there is something about the computer age or electronics or whatever – like a cylinder gramophone, some 3½” floppy disks, a poster of Sony products, or Bill Gates smirking over a couple of computers that were both surely far too old to run Windows XP!

In another room there are displays about some of the financial crises in history, such as the Great Depression, the more recent Greek financial crisis, financial ethics and, of course, the subprime mortgage crisis.

There are also words and pictures about Berni Madoff and an explanation of the Ponzi scheme.

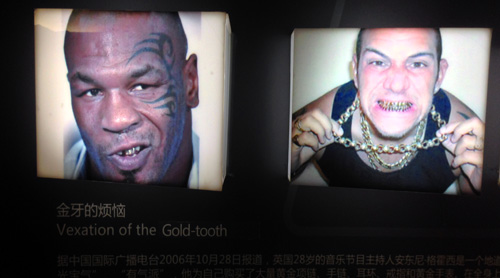

For those less enamoured by paper money and electronic transactions, there is always the lure of gold, whether you carry it around in your mouth …

… or sit on it to conduct your regular business

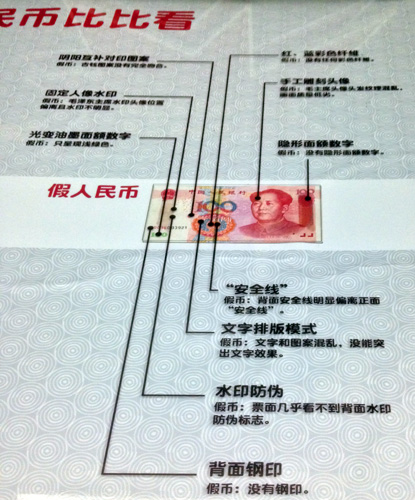

But at the end of the day it’s always good to know that we can rely on good old Mao stuffing up our wallets – though as this poster shows, you have to be wary of forgeries every time you receive or spend any money. Having had at least three forgeries pass through my hands here in Beijing (and had two thrown back at me – literally), I guess I should study this poster in a bit more detail. Or perhaps not. Now what did I do with my online translator?