A Visit to Marstons

I’m always amazed when talking to foreigners who have never been to the UK. They all want to visit London, of course; and many plan to visit other places on the tourist trails such as York, Wells, Brighton or even as far as the Lake District.

Never though will you hear a mention of anywhere in the Midlands, even for a day out; and it got me thinking that perhaps many miss out on some quite charming places simply because they don’t know they exist.

I can’t blame them of course. It wasn’t that long ago that I myself could only vaguely point out on the map where such towns as Lichfield were… Yet with its open spaces, historic centre and pretty views, it certainly makes for a nice day out…

It’s a very “green” place and one instinctively reaches for one’s camera, even on a cold November day, to capture the essence of the place…

It also has its quirky side, like most places I guess, if you keep your eyes open. This, for instance, is my favourite sign in the whole town. Need I say more?

So why am I telling you all this?

Well, first of all, it’s where my daughter Genevieve and her hubby have pitched up; and one of the reasons she lives there is that she works for a brewery company which, unsurprisingly, is located in the Midlands. If you go to the web site – www.marstonsbrewery.co.uk – you can see her smiling mug shot. Huh? Talented people? [I think this is where an emoticon for a proud parent should go!]

Marston's PLC is an independent brewing and pub retailing business operating around 2,100 pubs and bars situated across Great Britain and is the world's largest brewer of cask ale. It produces well over 60 permanent and guest ales from its five regional breweries stretching from the Lake District right down to Ringwood in Hampshire.

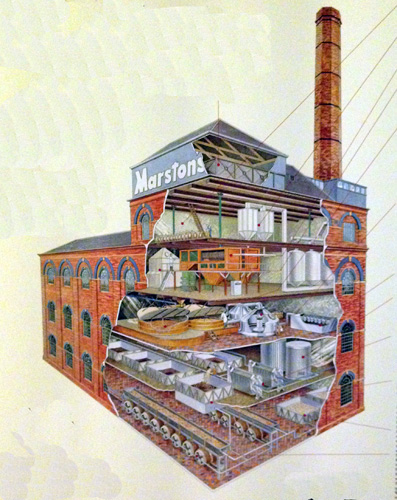

Marston’s Brewery started life as Marstons Thompson and Evershed in 1834 at Horninglow, a suburb of Burton on Trent. Its Albion brewery was built by Manns Crossman who came to Burton to use the local water, but then returned to London in the 1870s. What is now Marston’s moved to this brewery in 1898 owing to its superior size. By this time the brewery had a capacity of 100,000 barrels a year. What was Manns in London has now, however, turned into yet another Tesco supermarket; but Marston’s just keeps on brewing at the Albion.

If you’re a beer ignoramus, you might wonder what all the fuss is about with Burton-on-Trent. Well, it turns out that the town of Burton has several very successful breweries due to the chemical composition of the local water.

In the early 19th century, pale ale was being successfully brewed in London. But in 1822, the method was copied by the Burton-upon-Trent brewer Samuel Allsopp, who got a fuller hop character and ‘rounder mouth’ feel to the beer because of the sulphate-rich water he was using. The clean, crisp, bitter flavour of his beer became very popular and by 1888 there were 31 breweries in the town The characteristic whiff of sulphur indicating the presence of sulphate ions became known as the "Burton snatch" (no rude comments please!!!) which, it appears, is not dissimilar to the smell of struck matches.

A chemist going by the name of C. W. Vincent analysed the waters of Burton and identified the calcium sulphate content as being responsible for accenting the hop bitterness in Burton Ale. Many breweries outside the Midlands 'Burtonise' their water, meaning they add extra gypsum to get that fuller taste; and “Burtonisation” is used when a brewer wishes to accent the body in a pale beer, such as a pale ale.

Genevieve tells me there is nowadays an ever growing number of women who are coming to appreciate the taste of various beers. I often say to people what an awful job she must have – having to drink beer for a living! (Though in fairness there was a time when if she was asked what her dad did for a living she would say she didn’t really know, but she did know that I went to an awful lot of parties!) LOL!

Marston’s is probably best known for its priority products – Marston's Pedigree and Wychwood Hobgoblin.

I always used to think that one brewery was much like another. Sure, there will be subtle differences between different brews, but at the end of the day, brewing is all about producing beer through steeping a starch source in water and then fermenting with yeast, isn’t it?

Wrong! Little did I know that breweries like Marston’s keep what are basically recipe books containing upwards of 80 plus recipes for different types of beer. Everything from the type of grain, the hops used, the water, the yeast, the fermentation process etc etc etc has a part to play in the final product.

At Marston’s, a four roller Porteus mill grinds the barley and cleaves the husks off, crushing the innards into flour, revealing a starch/sugar complex inside. The crushed malt is called grist and this is added to hot water and the resulting mash is left to form a consistency of thick porridge.

The so-called wort is then boiled with hops for over an hour in a stainless steel kettle, called a copper (which is what they were made out of in the old days) to add bitterness.

Each of the three copper kettles here at the Albion holds 440 hectalitres - that’s 44,000 litres to me and other mere mortals.

The hopped wort is then pumped into a whirlpool where hops and protein 'trub' are removed. The bright wort is drawn off and cooled rapidly, ready for fermentation (the heat drawn off is used to heat the next batch of mash, BTW). Oxygen is also added to stimulate the yeast at the start of fermentation which then grows by feeding on the sugar converting it into alcohol.

They still have the old equipment used up until 2005 as a reminder of days long gone. The Mash Tuns go back to Victorian times…

as do the old coppers…

Outside in the still night air, the escaping steam gives off an eerie feeling to the place.

One of the things that makes this brewery unique, though, is something called the Burton Union fermentation system – a series of interlinked wooden union casks that has the beer dropped into them after two days of fermentation.

The idea was to prevent excessive beer and yeast loss through foaming, but one of the resulting benefits is that the beer is both in contact with more wood and in contact with more beer, as it ferments in a bigger volume, typically totalling about 100 barrels or 16 hectolitres; and this way it gets a more consistent oaky flavour and consistently good quality yeast. It’s used for Marston’s Pedigree which is one of Marston’s most popular brews.

The fermentation continues inside the casks and the CO2 that is produced by fermentation rises out through a swan neck on the top, taking yeast – that has been held in suspension in the beer – with it, and that way you separate the beer from the yeast, as well as getting some of the oak characteristics carried over into the final taste. The system was refined to separate any expelled beer from the wasted yeast, allowing it to flow back into the casks to continue fermentation.

As the yeast gets thick it collapses in onto itself and settles down. At this point it is raked off into a storage tank held at 4 degrees and the next week it is mixed in with the new brews and the recycling process starts again.

Here’s a pitching vessel ready for the yeast to be added to whatever it is needed for…

Marston’s has four storage tanks of yeast. If they get too much of the recycled stuff, it is shipped off to the Marmite factory down the road. (And that, I learned, is why Marmite is based in Burton on Trent!)

I mentioned Marston’s Pedigree, which is a bitter first introduced way back over 60 years ago. It is Marston’s flagship product, selling over 15,000,000 litres a year.

Some brews have stopped being made at Marston’s as I guess beer tastes come and go. But one of my favourite beers is an India Pale Ale, and Marston’s still makes its Old Empire which is one of the most popular styles in the UK.

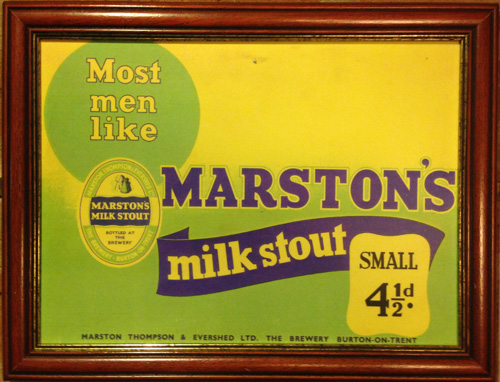

But another is Milk Stout which is very high in calories, as it uses lactose sugar which cannot be digested by yeast, so it has a creaminess to it and does nothing (good) for your waistline! And it has been consigned to the history bins, unfortunately.

Another firm favourite is called Dogs Bollocks. My take on this is that the marketing guys know how to sell a beer regardless of its taste. OK, it might be quite nice, but I suspect most people buy it for its name.

(To my American and Asian followers, who might be a bit confused by this name… “Dog’s Bollocks” in British English means something which is pretty darned good. Hence the British humour inherent in the name!) It sure guarantees comments when I wear my Dogs Bollocks T-shirt!

I asked if this room is where they kept the dog, but it appears Dog’s Bollocks is brewed at Marston’s Wychwood Brewery in Oxfordshire… oh and there is no dog here either! Maybe someone at Marston’s has a warped sense of humour?

Now, you might think that pouring a glass of beer is something anyone can do. But Genevieve takes me across to Marston’s own little private pub in the heart of the brewery itself to educate me a little more. This is definitely the kind of place where you COULD organise a piss-up in a brewery!

I was totally unaware that different types of beers require different types of nozzles and gases to ensure the perfect pint. Gen clambers behind the bar and explains that for hand-pulled beer you need a really firm but steady first pull; and you need to position the sparkler just below the surface of the beer to get a creamy head.

The sparkler, BTW, is a diffuser which forces the beer through lots of little holes to ensure that lots of gas can break out of solution and give the drink a creamy head. The nozzle effectively aerates the beer.

And with keg beer, raising or lowering the glass as you pour affects how good a head you get on your pint.

There’s something almost poetical about seeing a well poured pint settling down waiting to be in a fit state for drinking. It somehow adds to the pre-gulp enjoyment waiting for that moment, don’t you think?

I’m about to reach out to ensure that the demonstration samples are put to good use; but am not quick enough off the mark before Gen matter-of-factly pours them down the sink, on the basis that those were the ones which hadn’t been poured that well. But… but… but… I protest helplessly to my strong-willed daughter…

Now you know how to pour a decent pint, Gen continues, I feel I can now leave you to practise your new found skills… and apologising that she has to leave me for a couple of hours to get some real work done, she leaves me in the bar and tells me to help myself!

It’s not long before I make a new discovery – Marston’s Oyster Stout. Forget about Pedigree! This is the drink for me!

Maybe I’m a cheapskate, but when you hark back to the days of Charles Dickens and Victorian times, stout and oysters were considered a poor man's hearty meal. Well it appears that Oyster Stout is a great tasting traditional English stout that is designed to bring back the flavours of those simpler times – or so the advertising blurb would have you believe.

The unique character of Oyster Stout comes from its fermentation with yeast, taken from the Burton Unions, that we talked about earlier. Aromatic English hops such as Fuggles and Goldings are added for a fruity, floral and spicy taste with the bitterness coming as well from the roasted malts. The final result is a rich, dark and extremely creamy smooth stout which is… well… more-ish. Not to put too fine a point on it, I would say this is my favourite Marston’s beer without a shadow of a doubt.

All too soon, Genevieve hurries back apologising that she has kept me waiting for so long. No, no… feel free to do some more work, I protest; but it falls on deaf ears. It’s time for me to inspect the new bottling line that has only recently been installed.

To get into the bottling plant requires everyone to wear protective clothing; and your favourite blogger is no exception to the rule…

First I am togged up in steel toe-capped footwear with steel mid soles so I can’t get broken glass into my little tootsies; not that there should be any broken glass, of course, but one can never be too careful. I wonder if they have steel-capped footwear in size 11, but it appears that the brewing fraternity has seen no shortage of real men passing through its doors, and my size 11s present no problem for the stores.

High viz vests are also a necessity as there are fork trucks moving around at a great rate of knots; safety specs too are obligatory, as there is glass under pressure so breakages are always a possibility. A bump cap, too, must be worn as there are palettes everywhere and the occasional bottle dropping onto your cranium might be a trifle boring without a cap on.

We enter the bottling plant, suitably togged up. A prominent notice tells the fork-lift truck drivers to be aware of pedestrians… not, you’ll notice, that pedestrians should beware of fork lift trucks. This is definitely fork lift country and they have priority at all times. It feels a bit like crossing a busy road in downtown Beijing! You wait for a gap in the traffic and then stride your way manfully across the flow hoping you leave enough room between yourself and the next vehicle.

In no time we are standing in the middle of the bottling line. It is still being commissioned and Gen warns ominously that I mustn’t touch anything. And she means anything. Cleanliness is important here and they don’t want the germs and other detritus that your favourite blogger brings in with him spoiling the output.

I used to work in Saudi Arabia where one of my clients was a famous dairy products manufacturer, whose production facilities I used to visit. So I have seen bottling lines before. I guess that although some would have you believe that once you have seen one, you have seen them all, I find the whole set up sheer poetry-in-motion … sex on a conveyor belt … call it what you will.

Empty bottles are fed down slotted conveyors where they are washed, sterilised, and chug round to have beer squirted into their innards, after which they are sealed, and three labels – front, back and neck – are brushed on.

The bottles clank their way along more slatted conveyors …

rushing along through the bottling hall…

as they push their way forward to a tray and shrink wrapping machine, known as a kister.

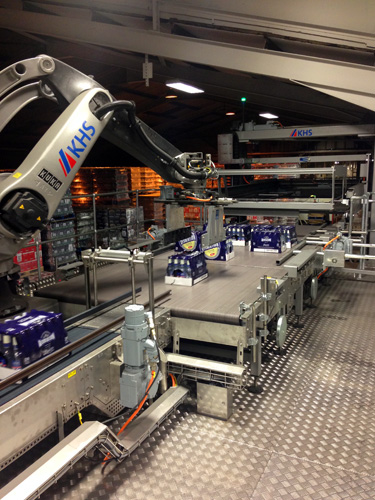

Helical conveyors are used for space saving when bringing the shrink-wrapped trays of 24 bottles to the robots, which gently shove and push their charges about.

The shrink wrapped trays are then collected together by another robot into palettes which are then stashed together and sent out for shipment.

The bottling line is like a well choreographed ballet… a ballet of robots with just the occasional prodding by their human operators to keep them on the straight and narrow.

Genevieve leads me out of the noise and into the peace and quiet of the sampling room, which is not normally open to the general public.

Along one wall are three shelves which have a display of bottles going back to the year dot, and featuring labels that haven’t seen the light of day for many a decade.

Apparently Marston’s has a book of recipes for over 80 beers, though they are not all brewed throughout the year, some being seasonal and sold only in the winter or over the Christmas period.

And some beers such as Hobgoblin have typically 24 different types of packs, depending on which country it is being shipped to, what time of year, whether it’s a 6-pack or 8-pack etc

In the sample room, there is also a pile of sample packets of hops from around the world. British hops mainly come from east Kent and Worcestershire; but now the rest of the world has jumped on the hop bandwagon and is now producing over 100 varieties.

Hops add bitterness and aroma to a beer. Technically speaking, they contain an alpha acid which is isomerised during the kettle boil which changes the flavour to bitter and also contains a volatile oil which can also be used to add flavour later in the brewing process.

My tour is over. As usual, there is far too much to remember of everything I have been told; but certain images stick in my cranium … the Burton Union with its recirculating yeast; the T-shirts featuring the bollocks of a dog; the sight of what look like perfectly good beer being poured down the drain; and the recurring image of yours truly practising the art of pouring the perfect pint while left on his own in the pub within the brewery.

Organise a piss up in a brewery? Hey, just ask the expert!