Sagada – Where the Dead Are Hung Up on Display

I have a lot of catching up to do. In the UK we were hardly told anything about the Philippines. It was a splurge of islands in the Pacific and that was about it. I don’t remember them ever being mentioned in school geography lessons; and as for history… forget it.

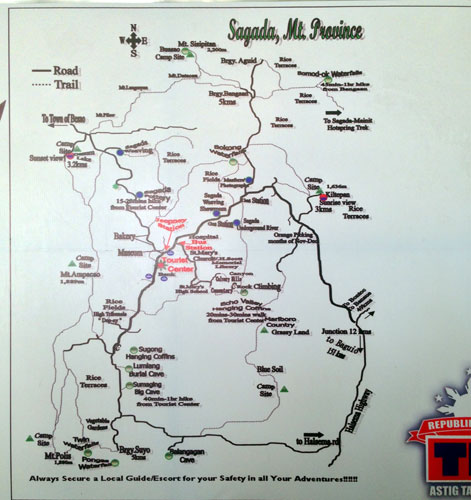

So the more I travel around the country, the more I keep on coming across things I have never heard of – and wonder why. Take Sagada, in Mountain Province, for instance. Located 275 kilometres north of Manila, 140 kilometres northeast of Baguio, and adjacent to Bontoc, the provincial capital, it has quite a reputation.

OK, some visit for its cool and refreshing climate; yet others to explore the labyrinth of caves there, but I am sure that not one single tourist doesn’t have their curiosity piqued by Sagada’s famous hanging coffins, of which more in a moment.

Sagada is a small town (though in European terms it would better be described as a large village) in the north of Luzon, in a valley at the upper end of the Malitep tributary of the Chico River, some one and a half kilometres above sea level in the Central Cordillera Mountains.

Perhaps for lack of transportation and willing guides, few conquistadors set foot in Sagada during the Spanish Era, and a Spanish Mission was not founded until 1882. As a result, it is one of a few places that has preserved its indigenous culture with little Spanish influence.

Between 1882 and 1896, the Spanish introduced Arabica coffee; and during the American occupation, lemons, limes and Valencia oranges were introduced to provide the needs of American missionaries. The Americans also introduced strawberries, peaches and apples, due to the cooler, highland rainforest climate.

The town only got electricity in the 1970s which is when tourism on a small scale started. The reason there were no hoards of tourists, according to ‘The Rough Guide to the Philippines’, is that the quickest way to reach it from the capital ‘involves at least one buttock-numbing bus journey on a terrifyingly narrow road’. Well, I think that is overstating it, though I can see their point.

Grabbing one of the many buses that head there from Baguio will take around 4-6 hours, with a short loo break – where you can also buy a coffee and donut – and then carry on winding your way up steep hills, around crazy corners, over a scenic mountain range, and even passing the highest point in the Philippines’ highway system. Throughout the journey you look down on all manner of steep terraces filled with rice and vegetables.

Eventually, you disembark in a small market square opposite the tourist information office, at which all visitors are obliged to register for the princely sum of 35 peso. (Without the official receipt, you aren’t allowed through to see many of the sights.) It’s true to say that Sagada lives for tourism, and tourists are milked unashamedly. Not only does everyone have to register, but the rules also state you must hire a local guide to visit practically anywhere, that’s when you’re not being encouraged to part with some more of your readies for souvenirs and provisions. But with overnight accommodation for two unlikely to set you back more than 500 peso, and with the many restaurants also charging a mere fraction of what it would cost you to eat in Manila, no one is complaining.

To see everything in Sagada would take you a good two days; to see it superficially will take a mere half day; but with the first buses arriving after midday, and with the last buses departing in the very early afternoon, you are likely to be spending at least 24 hours here, whatever your timetable.

The town is right in the heart of a pine forest. The smell of the pine is wonderful, as are the wild flowers and shrubs that greet you at every turn.

A gentle walk from the Tourist Office is the Episcopal Church of St. Mary the Virgin. This was the first Anglican church established in Sagada, and though the tour books advise you to check out its architecture, none of the tour guides want to stop here. Unlike the majority of the Phils, religion in Sagada and its environs is very much Anglican as opposed to Roman Catholic.

Though the church suffered damage during World War II when the Americans bombed the Japanese occupiers in the area, the people of Sagada were able to reconstruct and retain the original building design.

Outside, in the grounds, is a monument made up of two large iron wheels that were brought over from the USA as part of the sawmill restoration project and were discarded when the project ceased operation.

Moving on from the church grounds, and bearing left at the High School, brings one to a graveyard. There’s a poignant reminder of the recent ‘Maguindanao incident’ – a national disgrace if ever there was one, not least in the way that the politicians, right up to the President himself, have all been scrabbling to distance themselves from any part they played in it. There’s a newly constructed grave of one of the soldiers killed on January 25, 2015, when 44 members of the Philippine National Police-Special Action Force (PNP-SAF) were killed in an ambush, at the hands of Muslim terrorists in Mindanao.

But what most people come to Sagada for are not the normal graveyards, moving though they may be; instead, everyone is curious about the hanging coffins which are everywhere – if you have a sharp eye.

Echo Valley is the most accessible for these coffins and is so named because you can stand on one side and call out a hallooo-a-lo-a-lo-a-lo – with the return sound coming back at you from all directions.

From this vantage point, Sagada’s famous Hanging Coffins are but a five minute walk away.

Don’t see the coffins? It takes time for your eyes to get adjusted sometimes – but take the path downhill and you should eventually end up with a worm’s eye view from the very best vantage point – right beneath them!

The native Igorot practice of attaching the coffins to the mountain comes from a belief that underground burials isolate a person from the natural world. This is a traditional way of burying people that is still used to this day – but only for married people with grandchildren; and only if the deceased specified this way of burial before they died. Some of these coffins date back hundreds of years. They appear small as the corpses are laid in a foetal position. The chairs hanging with the coffins are sometimes referred to as death chairs. Apparently the dead are first bound to the chairs at their home and only transferred to the coffins after a period of three days.

Walking on, one goes through a small coffee plantation. The area is famous for its coffee which, as already mentioned, was introduced at the end of the 19th century.

There are even one or two coffee beans still attached to the plants, though obviously the harvest has already taken place…

Apart from hanging coffins, the other main attraction for tourists is caving. There are two principal caves that the tourists come for. The tourist bumpf advises that the tour through Sumaguing Cave can be a rather extreme activity. “If you are overweight or out of shape, you will most likely not enjoy this and/or not be able to complete this” it warns ominously. “Some of the crevices you go through are just too small. The guides are very helpful and knowledgeable, but they are your only real safety net, as you are hanging on the walls with steep drops beneath you throughout the tour. That being said, if you are up for adventure, you will definitely enjoy this.”

Rock climbing and white water rafting are also on the menu of things to attempt to do before you die – but be warned; if you’re not from the locality and you don’t survive the Sagada experience, you won’t be allowed to be hung up for the next couple of hundred years to be admired by Sagada’s tourists!

I am neither out of shape nor overweight, but discretion being the better part of valour, the ‘Underground River’ at Latang Cave appears a better option. From the Hanging Coffins, the guide leads us down the hillside to what is little more than a stream.

Approaching the cave, the water gets a little deeper, but it would take a lot for it to actually get you wet above the ankles.

The guide stops and takes about ten minutes attempting to get his oil lamp working. One wonders why, in this modern era, he doesn’t use an LED torch, which surely must be easier and cheaper than using an old paraffin lamp.

The next tour group with its own guide approaches, and this one does have an electric torch; we combine forces and feel our way through a pitch black cave as our guide uses his lantern to make sure he doesn’t get wet, while the rest of us are thankful for the second guide shining his torch in turn as each of us tries to find a secure footing in the rock-strewn river through which we are having to make our way. It takes 15 minutes before we see daylight again; and if this is the easy route, I am thankful not even having considered for one moment attempting the Sumaguing.

On the far side we find ourselves trekking beside muddy paddy fields, trying to keep our balance on the slippery paths.

And at last we come to the Bokong Falls which, apparently, is where Sagada locals learn to swim. The tourist blurb tells us that “if the water’s too cold, it’s still fun to stand at the edge and let the mist wash over you”. Hmm. I’m under-whelmed.

Instead, what does take my fancy is a shop selling home-baked cinnamon bread. The smell seduces one to enter through the main door, and for a mere 25 peso (35p or 50¢) you can be the proud owner of a cinnamon loaf that is not destined to last too long in this world.

The next day a new and better tourist guide leads us down some back alleys to one of the local ‘dap-ay’ – or stone circles where community matters used to be resolved. It’s little more than a filthy rubbish-strewn children’s play area now and once again an extreme feeling of underwhelm-ment takes over. The look on the tour guide’s face shows she is equally embarrassed to have brought us here. But it’s on the official route, so a rubbish-filled dirt area is where we go, before leaving it in search of better things.

Heading on further down the hill from the village centre (instead of uphill to Echo Valley) we soon get a wonderful view of beautiful limestone rock formations.

Wait for your eyes to adjust and sure enough, there is another group of coffins, making you wonder how on earth anyone actually managed to place them there!

We trudge further down the hill; and soon we are at the 2000-year old Lumiang Cave and another resting place for Igorot tribal elders. With the spread of Christianity, many locals have opted for Christian burials in a different cemetery. However, the elders’ coffins remain in this cave, protected by the current generation. These coffins – the oldest being some 400 years old – are simply laid down against a cave wall; and you can actually go up to them and touch them if you have a mind to.

Some of the more intact ones have carvings on their lids.

But don’t be surprised to see one or two of the coffins broken open with old age, complete with the remains of a body inside! This is earthquake country, and more than once the pile of coffins has collapsed to the other side of the cave, from whence they have been retrieved and re-piled against their original wall.

We retrace our steps back up to the road and head on further down the hill. A passing jeepney has loads of tourists atop the roof of the bus. I hate to think what the health-&-safety brigade in Europe would make of it, but here it is touted as a tourist experience not to be missed!

Over the edge of the cliff face is a spectacular view of the terraced fields.

A notice reminds passers by not to drop litter – or as it actually reads, ‘Cleanliness is next to Godliness’. I feel very clean today.

We approach Sumaguing Cave, just to get a glimpse of what we bypassed yesterday, I suspect.

Way down beneath us in the bowels of the earth is an intrepid group feeling its way down with the aid of a single torch. I feel glad to have wimped-out of the experience!

Even the well-worn staircase leading us down to this vantage point loses its appeal after the 100th step…

Instead, by common agreement we head for the Yoghurt House – a popular restaurant serving meals from breakfast to dinner. Specialities include varied yoghurt dishes and fresh local produce, which I guess is how they came up with such an earth-shattering name.

But I do have to wonder sometimes at people’s use of English. I mean – what on earth is the point of having an indoor restaurant in which you are not allowed any food and drink? Could this be a spiritual lesson for us all?