Where Chanticleer Meets his Match (or his Maker)

I was delighted recently to come across the following on quotegeek.com which sums up what many townies must feel like when they go back to discovering nature: Being woken up at dawn by the cockerels is not in itself a problem. The problem arises when the cockerels get confused as to when dawn actually is. They suddenly explode into life, squawking and screaming at about one o’clock in the morning. At about one-thirty they eventually realise their mistake and shut up, just as the major dogfights of the evening are getting under way. These usually start with a few minor bouts between the more enthusiastic youngsters, and then the full chorus of heavyweights weighs in with a fine impression of what it might be like to fall into the pit of hell with the London Symphony Orchestra.

That just about sums up living in the Philippines, though I’m not sure if the Manila Symphony Orchestra could rival the LSO. It’s funny, isn’t it. In the UK, noisy cockerels prompt the threat of legal action for being a nuisance. You couldn’t imagine that occurring in the Phils, especially as cockfighting, or Sabong as it is known here, is big business. Basketball may well be the number one sport in the country, but cockfighting comes in a close second.

I’ve even heard it said that in the event of a house fire, a Filipino would first save his fighting cocks before his wife; and someone has worked out that over five million roosters will fight in the country’s pits during one calendar year, while the Philippine economy is said to benefit to the tune of more than $1 billion a year from breeding farms employment, selling feed and drugs and, of course, betting on the outcome of fights.

After Louisiana became the last state in the USA to outlaw cockfighting, an influx of American breeders poured into the Philippines supplying most of the best fighting cocks, with prices for quality blood lines selling for anything from 8000 pesos to as high as 120,000 pesos (£1,700).

Cockfighting in the Phils has been around for hundreds of years, preceding the first arrival of Ferdinand Magellan in 1521. Many will tell you that sabong was introduced to the islands by the Spanish. Not so, since it was already flourishing in pre-colonial Philippines, as recorded by Antonio Pigafetta, the Italian diarist aboard Ferdinand Magellan’s expedition.

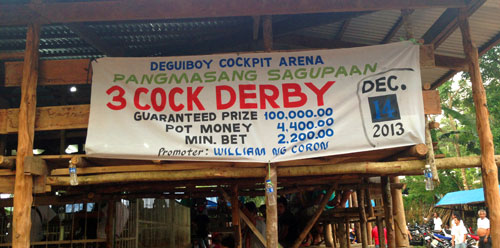

Cockfights are held year-round, though Sundays are the best day to go, and you’ll see notices advertising cockfighting derbies in even the smallest towns and villages.

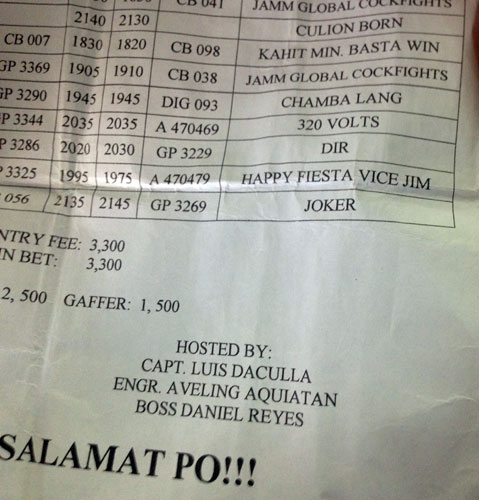

The fact that cockfighting is a vicious blood sport where two cockerels fight to the death – or one of them is critically injured – is not something that apparently fazes the average Filipino, though no doubt the animal rights lobby in Europe would have a field day campaigning against such inhumane treatment of animals. To make it “worse”, both gamecocks have sharp knifes, called gaffs, tied to the left leg, making the fights even more violent. Events typically last for an entire afternoon and well into the evening, during which 20-30 separate fights may be staged.

Anyway, as part of my induction into Philippine society I am taken to a local derby just outside town. You can tell you’re in the right place as there are literally hundreds of motorbikes and trike taxis parked by the side of the road…

Entrance to the derby is 200 pesos (£3), though my minder “knows someone” who turns a blind eye as we creep through a back entrance into the venue.

The sport of cockfighting is quite elaborate and is not dissimilar in some ways to the world of boxing where the birds are matched for size to ensure a fair fight. That’s where any similarity ends since it’s a fight to the death for at least one of the birds, though the winner might also succumb to his injuries sustained during the battle.

Someone hands us a programme listing the upcoming fights with the birds’ names, weights and other background essentials listed.

An old arena has ascending rows of wooden benches – the spectators climb up to the higher reaches, whilst most of the betting fraternity appear to prefer the lower levels. The names of the two contestants are scribbled onto green and orange paper before each fight and hung above the ring…

To ensure the birds get as aggressive as possible (cocks are notoriously territorial) the birds are made to ‘face-off’ by their owners thrusting their charges at the other cock, with some even being encouraged to peck the other repeatedly. The owners also show off their birds to the howling mob – a well deserved epithet, I think – and while all this is going on the ringmaster whips up excitement in the arena through a microphone while furious shouting and betting starts taking place.

Bets are taken by the “kristos”, an irreligious name given to them because of their outstretched hands when calling for wagers from the audience. Nothing is written down – the kristos work purely from memory. They use a system of complicated hand signals across the room – a bit like bookies at a horse race in the West. It’s all deadly serious as many hundreds of pesos are waged in the process and the winnings – or losses – can be worth a lot more than the average monthly wage.

Sabongs are judged by a referee called a sentensyador or koyme, and his verdict is final with no appeals allowed. Before each fight he inspects the birds and checks the metal knife blade that has been carefully attached via a cloth binding to each of the contestants. When he is satisfied, the two birds are placed in the centre of the ring and the owners move well away to the corners out of harm’s way.

At first, the two cockerels strut their stuff, a bit discombobulated by the screams of the crowd who are lusting for blood.

But soon the two fighters notice one another and quickly circle in to let the other know they are trespassing on THEIR territory.

One second it is peace and quiet (from the ring); but the very next there is a flurry of activity as the cocks fall onto one another in a blur of feathers and flashing blades…

After only a few seconds, one of the roosters starts to hobble and fall to the ground.

But just like in Western boxing and wrestling, the referee checks to see if it is a clean knock out, or whether there is still any fight left in them. There is. He picks them both up and throws them at one another a second time and there is another flurry of feathers. This time the one that appeared to be the underdog has found new strength and he lashes out at the other who might have been just a bit too cocky for his own good (pun intended!) and succumbs to a deadly lashout of his opponent’s left foot.

It’s all over bar the shouting. Once again the referee steps in and picks up the dying bird and drops it three times to the floor, just to make sure it really isn’t going to make another come back. It doesn’t, and the winning bird is returned to its owner, while a still quivering corpse lies in the centre of the ring.

The whole fight has typically lasted no more than about 90 seconds. The winner will almost certainly have sustained some injuries from the fight, and his owner takes him round the back to a chicken surgeon who will sew up between up six and 10 roosters in a day, for which he charges 200 pesos (£3) per bird. If it dies, there is no charge. Instead, it is quickly feathered and cleaned and in no time at all it has become a delicious adobo, or chicken stew!

The winning cockerel, assuming it survives, will now be pampered by its owner for the next few months until it has made a full recovery – after which it will once again be ready for the ring, older and wiser for its next fight!

But this ring is already being prepared for the next bout. A sweeper clears up the old feathers and drops water onto the blooded sand before swishing it all level and clean.

The next contestants are brought into the ring; the cocks face off to one another; the betting starts again in earnest; and almost exactly 15 minutes after the end of the last fight, carnage once again is let loose.

I have to say that I cannot claim to have enjoyed the experience – it’s very bloody and reminiscent of the Roman gladiator fights you see in films like Ben Hur and their ilk. But I guess it is an inseparable part of the basic Philippines culture. I don’t think you can condemn something until you have experienced it and started to understand what it is all about. But equally in the same way I can understand the argument that if people didn’t go along to have a look in the first place, then it wouldn’t encourage the sport. (Mind you, I cannot believe for one moment that my presence there or not would have made one jot of difference to the people there.)

It is easy to condemn something out of hand; but can anyone tell me why on the one hand it should be wrong to get birds to fight to the death (something that their inbuilt aggression has “programmed” them to do) whilst it appears perfectly acceptable to very many people to pull fish out of the water by lodging a hook in their mouths – all in the name of sport.

I think we just have to accept the fact that man, as a species, has a lot of shortcomings, of which cruelty in the name of sport is just one.

But it was interesting to note that about 99.9 per cent of the spectators were men. (I only saw one female present.) What can be read into that little fact, I wonder?