Shanghai's Amazing Little Museum

Blink and you might miss it. In Shanghai, there’s a tiny museum tucked away in the basement of a block of flats in the former French Concession area. Hardly any of Shanghai’s residents have even heard of the place, but if you are an avid reader of Trip Advisor, the chances are that sooner or later you will make your way to 868 Huashan Road to see what T.A.’s readers have ranked as the sixth best museum in the whole of China – even higher than the National Museum in Beijing.

It typically attracts around 50 visitors a day, the vast majority being foreigners. From the street you’ll get very few clues that you’ve come to the right place.

But once you’ve nodded to the security guard, snoozing away or drinking tea, in his entry hut, and peered into the distance, you might be able to see a black-white-and-red sign letting you know you’ve come to the right place.

Yes. The ‘Shanghai Propaganda Poster Art Center’ is down a flight of stairs, in the basement, right next to the toilets. (If you don’t see the signs, simply follow your nose!)

Featuring some 400 posters dating back to the early part of the last century, it was set up by Yang Peiming and provides a unique insight into China’s recent past. It’s the only museum of its kind in the world – certainly as far the range of posters it has on display is concerned.

The collection of posters goes back as far as the early 1900s, and all the way up to the 1990s. As a reflection of modern Chinese history there is simply nothing to beat it.

What is, in effect, a somewhat damp and dirty basement apartment is used to display the posters, albeit that some are simply propped up against the walls. Most are covered with plastic, presumably to protect them, but which unfortunately means that you have to view them through the reflections of the fluorescent strip lighting overhead.

Yang began his personal collection (which now runs to well over 6,000) in 1995, buying the posters from printers, bookstores and publishing houses nationwide, as well as at auction. As there is not nearly enough room to show off his entire collection, he apparently changes what is on display on a regular basis.

As few peasants had televisions, let alone access to multimedia that is so common these days, these posters provided the principal means by which the Communist Party informed the masses and exhorted them to action.

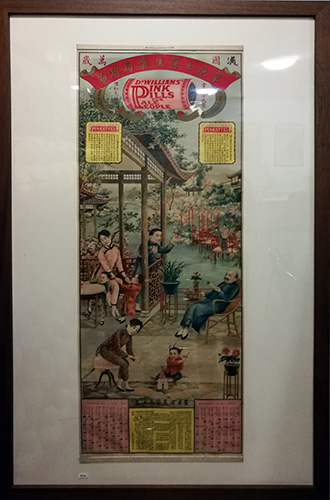

From 1910 to the 1940s, Shanghai posters were used to promote western goods such as cigarettes and beauty products.

They often showed fashionable ladies and married ‘art deco’ with traditional Chinese brush painting.

The Shanghai posters were to have a strong influence on what was to follow, as did some of the cartoon magazines, although they were to contrast sharply with the ‘Red Art’ style of the Cultural Revolution that make up the majority of the display. Many of these 1930s artists were to become propaganda artists after 1949.

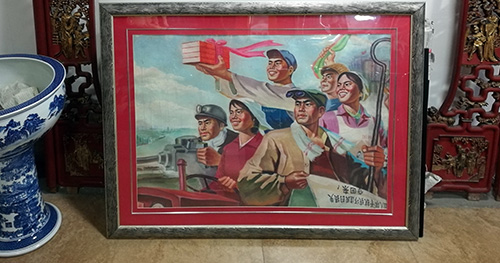

From 1949 to 1953, these artists were encouraged to celebrate the birth of a new China and many produced artworks which appeared to promise happy times ahead. Many of them had already produced poster art supporting the anti-Japanese war and the crusade for liberation. Most of the propaganda posters produced during this period were printed by privately owned plants in Shanghai.

The next three years were, politically, relatively stable and the propaganda posters of the time were mainly concerned with improving industrial and agricultural production and the promotion of family life.

However, from 1957 until 1962 political movements started to mobilise public opinion, and many caricature images of cartoon style posters were created by workers and farmers, reflecting the zealous enthusiasm of the common man.

This one from 1957, for instance, reads ‘Smash the attack by the rightists and defend socialist construction’.

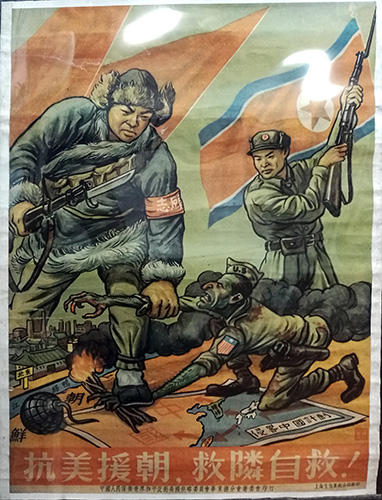

The Cold War was probably at its worst from 1963 to 1965 and many of the propaganda posters promoted opposition to ‘US imperialism’, epitomised by both the Korean and Vietnam Wars.

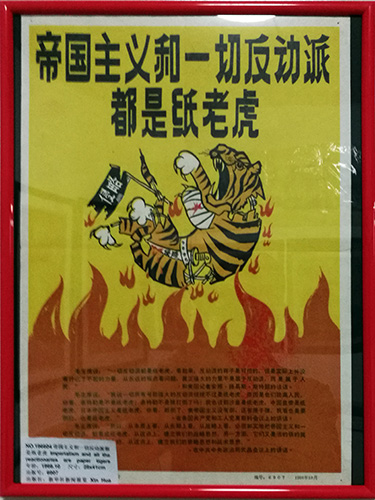

There’s even a poster depicting one of Mao’s favourite analogies that imperialists and reactionaries are paper tigers. All reactionaries are paper tigers. In appearance, the reactionaries are terrifying, but in reality, they are not so powerful. From a long-term point of view, it is not the reactionaries but the people who are powerful.

In the summer of 1966, the Cultural Revolution broke out in Peking University. In poster art, Chairman Mao Zedong was depicted as a red sun shining down on his people, who were often depicted as sunflowers.

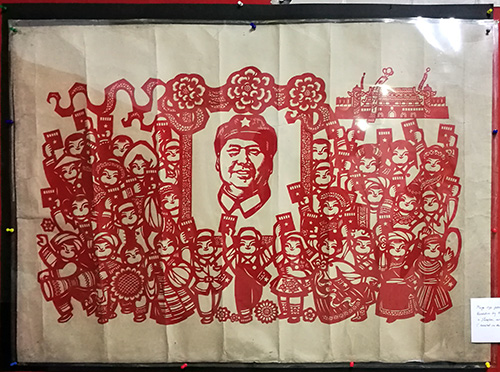

1966 also saw the first appearance of giant paper cuts featuring Mao surrounded by adoring peasants.

Common themes of the posters in this decade included world revolution against US imperialism, the rejection of Russian revisionism and the relocation of students to the countryside.

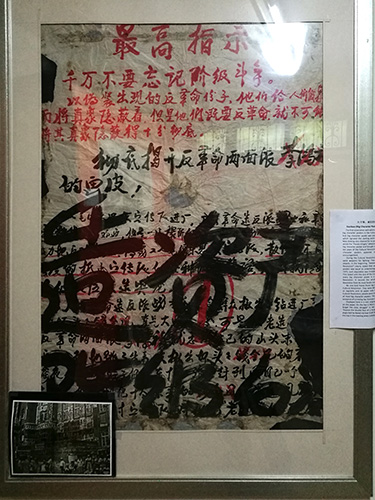

Yet another aspect of this era was the emergence of the so-called Big Character Poster (大字报 – DaZiBao). During this period literally tens of millions of big character posters appeared in China due to Mao’s encouragement. They were projected as sacred objects and vandalising a big character poster was viewed as undermining the movement. As a result, they were left in the street to natural erosion which is why they are so rarely found today. Yang Peiming has about 300 pieces of DaZiBao in his collection.

Although entrance to the museum is 25 yuan, it earns a little extra through the sale of reproductions of some of the posters, along with copies of Mao’s ‘Little Red Book’, Mao statuettes and other objets d’art of interest to foreign visitors.

Many of the visitors end up buying a calendar, or a poster catalogue or poster reproductions as a souvenir of this amazing collection.

Although this collection will only take you about 15 minutes to walk around, it amply demonstrates the artwork behind the Communist Party political posters and in so doing gives an extraordinary insight into the momentous events of China’s modern history over the last century.

** To find the Shanghai Propaganda Poster Art Center, take Metro Line 2 to Jiangsu Road and leave by Exit 3. Walk 300 metres east and turn right onto Zhenning Road. One km later, at the cross roads, turn right and walk for 150 metres. The museum is at 868 Huashan Road. Look for the PPAC sign on building 4.